What's in a name? Professor Oddie James Cox

Are you familiar with the given name Oddie? While researching the segregated Black schools of Western North Carolina, I discovered one of Ashe County’s (N.C.) educators: Professor Oddie J. Cox. His first name filled me with curiosity. Why would the name Oddie be given to a newborn baby? I googled that name and learned Oddie is a popular German name meaning “wealth.” While exploring the accomplishments of this educator, I became convinced that his life brought an abundance of riches to the students fortunate enough to learn in his classroom. However, historian Jeff Beckworth documents a local tale that indicates that because his mother thought her baby looked “odd,” she named him Oddie.

Photo from private collection

Photo from private collection August 24, 1893 — April 15, 1960

Public records indicate that Oddie’s ancestors were slaves belonging to the Aras Cox family, who, even after becoming freedmen, continued to live on their previous owner’s land and adopted his surname as their own. On August 24, 1893, Biddie, who was only 13 years old, gave birth to a son: Oddie James Cox. Oddie’s father was Jesse Reeves, the son of former slaves─ James and Fannie Reeves. Jesse and Biddie had been neighbors, living only about a mile from one another. The two young people became sweethearts, but, despite their shared child, the couple never married.

Young Oddie learned to read and write in the first few grades at Ashe County’s local elementary school for Black students, but poverty hindered his pursuing a formal education after learning the basics. Because he was the oldest in his family, Oddie, from a very young age, helped support his mother and his siblings. While in his early 20s, he discovered that he could earn a larger income by working in the mine fields of West Virginia. Oddie moved there and worked for the United States Coal Coke Company. Mining was a rough life, but the income was good. Then two events forced Oddie’s return to Ashe County: the death of his grandmother in 1913 and her husband’s departure from their home. Oddie returned to North Carolina to care for his brothers and sisters (accessed January 8, 2024).

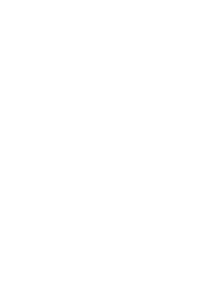

There he found neighborhood youngsters who needed help with their lessons, and Oddie began working as a private tutor. Before long, Ashe County’s School Board offered him a contract to work as a full-time teacher. By 1918 he was teaching at an all-black school in Pine Swamp. He found his work rewarding and wanted to do a better job of teaching. His solution was to enroll in college classes during the summers at the Agricultural and Technical (A & T) College in Greensboro, North Carolina. Beginning at the age of 46, Oddie commenced his study of basic subjects such as arithmetic, spelling, and writing. Then, for 23 consecutive summers, he added to his knowledge in the fields of botany, biology, chemistry, geography, and child psychology. Oddie selected courses not to acquire a degree but to build up his scholarship in fields that would interest or be especially useful to his young students. His purpose was to enhance his knowledge in subjects which appealed to the youngsters he taught. For example, he studied music and learned to play the piano in order to support his pupils’ keen interest in music.

From the beginning of his life Oddie, like other Blacks, was oppressed by the laws of segregation. For example, he was turned down when he first attempted to register to vote in 1940. His income, and that of other Black teachers, was barely a livable income. His salary was a mere fraction of those received by White educators. Oddie was not motivated by the money he received, but by the opportunity to help his students learn. In later years Ashe County residents recalled that the Black teacher attended basketball games held in the White gymnasium as well as Sunday meetings at the local Methodist church. He made a conscious effort to keep a “respectful” distance, whenever he was in the presence of White people. accessed January 9, 2024

A dedicated educator, Oddie taught at various Black schools for over twenty years while also serving as an administrator. After the close of World War II four one-room schools for Black learners existed in Ashe County. Officials allocated $50 to each Black school, but White schools received substantially more. While Black teachers earned an annual salary of $530, the White teachers received $1600 (Ibid,). There were, of course, fewer students in the Black schools, but preparation time was essentially the same. Black teachers dealt with challenging levels of learning in their classrooms, a situation that made individualized instruction a must. That same situation was also true in the White schools. Although funding was far from adequate for Black schools, the White schools deserved more than was allotted for their budgets. Education in Western North Carolina was not a primary concern of the state officials who handled school finance.

Oddie enjoyed spending time with youngsters outside the classroom. Interacting with his students was a fulfilling part of his life. He welcomed devoting personal time for their benefit. One example is his organizing camping trips for both Black and White youngsters. He required the parents’ permission for those weekend excursions. On other occasions the boys gathered at his place to play an “integrated” game of baseball or basketball. And he made time available to tutor any pupil who required individualized attention.

By 1947, when he was in his fifties, Oddie launched a campaign to improve Ashe County’s educational opportunities for Black students. By earning the support of the White superintendent of schools, A.B. Hurt, Professor Oddie Cox brought about much needed improvements. The school board listened to him clamor for needed changes, but he also had to persuade small Black communities to close their neighborhood schools and allow their youngsters to attend a larger consolidated and more centrally located school. One local citizen came to the rescue. Will Reeves’s gift of two acres of land in the Bristol village, not far from Jefferson, North Carolina, determined the location of a new consolidated school. Unfortunately, the new school had not been well constructed and leaked during rainy days or was poorly heated during the winters. Not even one typewriter was available, and both students and faculty used outhouses. Indoor plumbing was not available.

Oddie waged a campaign to have the new school named Bristol Central, which somewhat eliminated the stigma of being called the “Black school,” a designation which often denoted inferiority. The Ashe County Historical Society also identifies Oddie as both the school’s bus driver and its janitor. He bought a panel truck in 1948 to use as a school bus. According to the same article, Oddie served as a lunchroom worker because he prepared noonday meals for his students. During any snow days during the winter months, Oddie used a homemade plow pulled by a team of mules to clear the snow in order to allow access to the school entrance. “By 1960, Oddie served the Black students at Bristol in every possible capacity: teacher, tutor, coach, musical director, cafeteria worker, janitor, bus driver, and principal” accessed January 9, 2024.

On a Facebook entry for September 8, 2016, Shirley Baker shared this memory of Mr. Oddie Cox: “He seemed to always come to the Riverview basketball games. He would sit in the top bleacher behind the pot belly coal stove-the hottest place in the gym. Many of us (children) would gather with him. I don't remember much conversation-just a sense of comfort in the midst of such great love….” Other acquaintances of Oddie also described him as a caring man who longed to open avenues of knowledge to his students, as well as to himself.

Oddie continued his own pursuit of knowledge. He continued to enroll in classes during summer breaks. After studying subject after subject, the Professor built up a “greater than impressive” number of college hours. His decades-long pursuit of learning came to the attention of A&T’ s Acting President, Warmoth T. Gibbs, who approached members of the college faculty to gain their approval to award a degree to Oddie Cox, a life-long student. The faculty unanimously endorsed the proposal. Not a single dissenting vote was cast. The delighted Oddie was given the option of either having his bachelor’s degree mailed to him or attending graduation ceremony and receiving it from the president on stage. Oddie decided he wanted to walk across that stage to take part in the official graduation, and that is the message he sent to the committee at A&T University. Sadly, that is not what happened.

On April 15, 1960, a fire broke out in his home, and he perished. His neighbor, Ray Phillips, noticed a glowing light above the tree line, not far from his own front porch, in the direction of the Professor Oddie’s home. He rushed to investigate and found Oddie’s body just inside the front window with suitcases that were packed beside it. The dedicated teacher had died of asphyxiation while attempting to escape the blazing inferno.

At his well-attended funeral, both White and Black neighbors showed up to grieve at his passing. His memorial service was conducted by four ministers, both White and Black. And there were six pallbearers, three White and three Black men. Although Ashe County’s schools had not been integrated, Oddie’s funeral certainly was. And, upon examining his life, true to his German name, Oddie brought a wealth of opportunity to his students, both in and out of the classroom. Even 65 years after his death, stories of the Professor continue to be shared in Western North Carolina. His was a well-lived life, and his story continues to be honored in the annals of Ashe County, North Carolina.