The Kingdom of the Happy Land

Like the desert nomads, newly freed slaves wandered hither and yon throughout much of the war-torn South, often lingering near a turnip field or any site that offered food or shelter. In their former life as a plantation owner’s property, food and shelter was normally a given but having been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the South’s black citizens were on their own, no longer in bondage to nor provided for by their white owners.

Such liberty brought challenges the former slaves had not anticipated. With the dawning of each day, those wanderers faced the need to find food, deal with weather conditions, and decide which way to go. Should they keep to the path near a stream or strike out on an overland route? At times a leader would make those choices for the wayfarers. Although individuals could choose to go their own way, few were brave enough to journey alone. Although the travelers were no longer slaves, they had few choices. Simply surviving was a constant concern. One group living in Mississippi became motivated to create a kingdom of their own. That goal became their quest.

Oral tradition relates that a group of former slaves assembled at a plantation in or near Mississippi and accepted William Montgomery, a man freed from slavery at birth, as their leader. Elders interviewed by historian Sadie Smathers Patton (1957) claimed that William’s young mother, a black woman impregnated by her master, had been freed prior to his birth and that her little boy, due to his father’s generosity, had received a formal education, unlike other freedmen on the estate. The father endowed his son with land and a few slaves. Such generosity indicates that William had found favor with his white father.

With no treasures left and with no masters to provide for their needs, the newly formed group analyzed their options. Remaining in a community where their freedom might be challenged was troubling while the prospect of relocation provided them with hope for a better future. Driven by the idea of creating a utopian community governed by the concept of “one for all and all for one,” they journeyed across Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina and allowed other hopefuls to join them all along the way.

Survival required great diligence. Food was a constant concern, and finding a field with potatoes was a godsend. Abandoned animals could lighten their load, because the travelers could share a horse or mule to transport either themselves or their goods across many miles. In upstate South Carolina, the wanderers heard of vast stretches of uninhabited mountain land to the north and decided to seek their fortune there.

Following the Buncombe Turnpike into North Carolina, they arrived at Oakland, an estate owned by Serepta Merritt Davis, widow of Col. John Davis, whose family had operated a stagecoach stop. Widow Serepta was a hospitable woman, with a well-earned reputation for generosity. The wanderers were fortunate to stop by her home. She provided them with food and offered to let them remain on her land in exchange for labor, which was sorely needed to restore Oakland to a degree of prosperity. It was a great opportunity for the group. Their journey had finally ended.

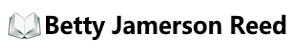

On the Davis’s huge estate workers found plenty to do in exchange for a haven. They willingly plowed fields, planted crops, and repaired dilapidated buildings, taking time to erect log cabins for themselves. However, in 1882, Montgomery was able to purchase 180 acres of the Davis property at $1 per acre. There he and his followers created the Happy Land community. In accordance with their philosophy of “all for one, and one for all,” its members placed all their money into a common treasury to be dispensed as needed by their king. The Kingdom dwellers looked out for one another. The deed identifies both Robert and Luella Montgomery as the legal owners of the Happy Land property, which spanned the border between North and South Carolina.

Frank FitzSimons (1975), noted Henderson County (N.C.) historian, attributed the Happy Land residents’ push to find a site for the "kingdom" resulted from their longing to live as they pleased, with few restrictions, in a kind of utopia. The Happy Landers gave their leaders the royal titles of king and queen. One king was the unmarried Robert Montgomery, who appointed his sister-in-law, his brother’s wife, Luella, to serve as Queen of the Happy Land (Patton, 1957).

The Kingdom’s extension across state lines proved to be a wise choice because trouble in one state might be avoided simply by assembling on the section of property located in the neighboring state. Ed Bell of Blue Ridge Community College laughingly told reporter Harrison Metzger that legend suggested the Happy Landers’ moonshine production invited raids from law enforcement. By simply retreating across the state line, citizens of the Kingdom were able to avoid arrest (“Former slaves founded Kingdom of Happy Land,” Times-News, February 22, 2004), an alternative to which their white bootlegging competitors had no access.

Whether true or not, such tales lend credence to the community’s existence. The Happy Land residents found themselves welcome at St. John in the Wilderness, an Episcopalian church, opened in 1836 and originally constructed as the chapel on the Charles Baring Estate in Flat Rock. Members of Kingdom occupied the back pew. The Rev. William King ministered to their spiritual needs (Louise Bailey, PC, January 18, 2006). East Flat Rock native William Darity recalled that both his grandmother and his mother mentioned the Happy Land Community. Retired educator Hortense Potts also documented accounts about the Kingdom shared by her father, as well as by other members of the East Flat Rock community.

One descendant, William Judson King, verified his family connections with the Kingdom during interviews with members of Henderson County’s Black Research Committee and Gary Franklin Greene (1996). King’s grandparents, the Perry Williamses, threw in their lot with the band of freed slaves and joined the Kingdom after it had established roots in Henderson County. However, by the turn of the century, they had resumed residence in nearby Hendersonville.

In their unique commune, the freedmen established a tradition of schooling. Having finally found a place to establish homes, the community made educating their youngsters a priority. In the 1880s and 1890s, Luella Montgomery taught the Happy Land children reading and writing by using Bible stories and songs (Greene, 1996). Mary Couch Russell shared memories of Louella’s lessons with Sadie Smathers Patton (1957).

As a small child playing in her yard on the hillside, Mary could see Louella beckoning the children to assemble for their lessons. She would race down the hill to join the other students. There Louella would instruct them and lead them in singing spirituals and other songs. Her “field trips” included taking the children to sing at the homes of white people living nearby, where they received an enthusiastic welcome. Louella’s lessons often focused on religious instruction.

Mary Couch Russell and her brother Ezel Couch remembered, that after reaching a certain age, they, along with other older Kingdom students, were sent to a school conducted by the Reverend Walter Allen in a place known as Possum Hollow. Allen, a former slave, gained his reputation by teaching and preaching at various sites in Henderson County (Patton, 1957). In Henderson County, evidence exists of educational opportunities for black children in one form or another dating from the time of the Civil War.

The Happy Land Kingdom survived from approximately 1864 until shortly before the turn of the century. The pilgrims lived there until challenging economic conditions forced most of them to move away to find employment. Until then, their kingdom was a haven for all its residents.

By 1870 the Kingdom was well established and prosperous. Being located near the Buncombe Turnpike allowed ease of transporting goods produced in their community to the marketplace and permitted those who sought outside work to travel back and forth with ease. Zircon mines, located nearby, provided jobs for many willing workers. Harvesting timber was a steady source of income, especially while the railroad was under construction. Any Happy Kingdom products, such as liniment, could be hauled to nearby markets to the north and south.

Why such a community was established and why it ceased to exist has aroused speculation. William Judson King, whose grandparents resided in the Kingdom of the Happy Land, asserted that the "kingdom" was an attempt to preserve African traditions and treasured customs originating from their ancestral roots. King, whose view was shared by East Flat Rock native Ernest Mims, attributed the commune's disbanding to an economic crunch caused by new technology that eliminated the need for their skills from the marketplace. To survive in a hostile economy, they abandoned the Kingdom to secure employment elsewhere (Greene, 1996). Gary Carden (2009) claims its demise resulted from the coming of the railroad which eliminated most commercial travel on the Great Road which had brought the travelers to Oakland. According to Carden, there was no longer any economic alternative, and the Kingdom was abandoned.

n the 1950s, half a century after the Kingdom’s demise, Sadie Smathers Patton, a historian, compiled a saga of the band's pilgrimage and its colony. After its inhabitants moved elsewhere, remnants of the community could be found on site and have been documented in articles in the Hendersonville Times News. Staff writer Harrison Metzger located vestiges of the compound while researching an article used for a black history feature in the February 22, 2004, issue of that newspaper. While preparing “Former slaves founded Kingdom of Happy Land,” Metzger discovered piles of rocks, remains of a chimney, and periwinkle — a plant believed to have been propagated by the original settlers — on the Kingdom land, which was acquired in 1910 by Joseph Oscar Bell.

One of only two kingdoms ever to exist in the United States, the Kingdom of the Happy Land became the victim of economics. With no demand for their services or products, its citizens were forced to wander once again, but this time, for employment. The families abandoned their homes in order to survive, but, for a while, their Kingdom thrived.

End Notes

Carden, Gary. - Accessed December 16, 2023. Izard, Mistyn Craver. - Accessed January 16, 2024. Reed, Betty Jamerson. School Segregation in Western North Carolina (McFarland Publishers, 2011). Smathers Patton, Sadie. The Kingdom of the Happy Land, (1957) Frank FitzSimons. From the Banks of the Oklawaha (Golden Glow Company, 1975). Greene, G.F. A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County Asheville, N.C.: Biltmore Press (1996).Published

Virginia Writers Club Journal 2024