Homeland Invasion!

World War II marched into East Flat Rock, North Carolina, following the Spartanburg Highway south out of Hendersonville, stepping past Rozier’s Curve across the porch and into our home. On December 7, 1941, I was enjoying the life of a four-year-old, but I recall stories of “Japs” bombing Pearl Harbor. Four days later Germany declared war on the United States, and later its U-boats lurked off the North Carolina coast.

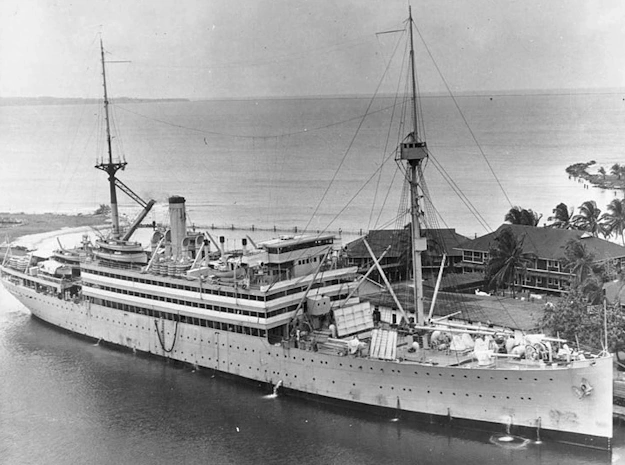

Shortly after the carnage on Oahu, Gromer Luther, who lived with our family, left East Flat Rock on a train headed to San Francisco, where he climbed aboard the USS Henderson and crossed the Pacific to land at Pearl Harbor. There he worked in a civil service office until the war’s end. During his absence, whenever a train whistled in the distance, Mother frequently remarked that its lonesome sound reminded her of Gromer. He was gone, but not forgotten.

The domed-top radio in the living room played a vital role in our lives during the war. Mother became immersed in the trials and tribulations of Stella Dallas and Helen Trent. She sang along with Gene Autry, but I perked up to listen to his adventures with his horse, Champion. On Saturday mornings I would stand on tiptoe with my ear pressed to the radio and enjoy the latest Let’s Pretend show, which opened a magical world for me. When he was home, Daddy never missed the news.

Any scrap of information about the war was important to our community. There was a nightly newscast, but the reception was often poor. Neighbors stopped by to discuss the latest reports. I remember the day Harley Justus, the neighborhood veterinarian, stopped by to visit. While he and Daddy were sitting beside the house in straight-backed chairs exchanging news and discussing Victory Bonds, he removed a huge chunk of chocolate from his pocket, cut off a piece, and put it into his mouth. I stepped up to his side and begged for a piece of that candy. “Are you sure you want it?” I insisted I did. He pulled out the chocolate and cut a piece for me. When that plug of tobacco touched my tongue, I could not spit it out fast enough. The heartless men chuckled over my dilemma. World War II ended my experience with tobacco!

On Saturdays, Mother stood in line to buy tickets at the theater in Hendersonville. She wanted to watch the weekly newsreel. I recall battle scenes with airplanes dropping bombs and tanks rolling across battlefields on the screen, but my most vivid memories, and my first experience with “cliffhangers,” are of heroic cowboys in those serialized movies that followed the news. Talk of “the war” was so common in my childhood that world affairs did not trouble me. I was more interested in helping Daddy take our cow, Daisy, to new grazing fields, wading in the creeks, exploring the swamps, and learning to play checkers.

My childhood was just that−−childhood, but the war altered our family’s lifestyle and even the interior of our home. Black shades replaced white ones at each window. Daddy would occasionally tell Mother, “Tonight there will be a blackout.” That evening they would pull all our shades down. No electric lights were turned on. My folks made sure not a glimmer could be seen by enemy pilots that might be circling overhead, but the youngest member of our family had no appreciation for being in the darkness. Peggy Jean, my two-year-old sister, cried loudly and seemingly nonstop. Occasionally, after multiple attempts to soothe her, Mother would light a kerosene lamp and place it on the kitchen table to calm our shrieking toddler.

Peggy’s asthma attacks challenged the order for a blackout. Even with her chest slathered with Vicks salve, she needed help to breathe. Our folks draped bed sheets over chairs and boiled water on a hotplate to create moist vapors so Peggy could breathe more easily.

Ration books highlight my memories. Whenever Mother bought groceries or gasoline, she had to present her ration stamps, along with cash, to make the purchase. At the gas station, she would tell the attendant, “A dollar’s worth.” After he finished checking the oil, cleaning the windshield, and pumping gas, he would take her money and tear a stamp out of the book. She would murmur “Much obliged” as she returned the precious coupons to her purse. Canned goods, meat, and tires were included in the “rationed list.” Buying shoes to wear to school (bare feet were not allowed) required parting with more stamps. When canning season came, Mother did not buy sugar for her preserves, jams, or fruit. She hoarded her stamps for gasoline and tires.

My school days commenced in 1943 when I enrolled in the first grade, as my brother William (I called him “Bubba”) began his final year of high school. This new phase of my life strengthened the war’s impact on me. Mother asked “Bubba” to drop me off at school on my first day. We climbed on the bus at Rozier’s Curve, and soon the driver pulled into the elementary school parking lot to pick up other high school students. My brother stepped off the bus with me. Lifting his hand, he pointed to double doors at one side of the school building and said, “Go through those doors and wait until you hear a bell ring. Then go into the first room you see. That’s the first grade.” I did as I was told, and, when I walked into the classroom with other first graders, two teachers lined us up around the room and took turns picking the students for their classes. I felt relieved when Miss Edith (Hart) pointed her finger at me and said, “I’ll take her.” She had been my brother’s teacher.

From day one, Miss Edith engaged us six-year-olds in the war effort. She taught us to pledge allegiance to our flag and to pray for our soldiers. She gave each of us a stamp book and, by saving our nickels, dimes, and pennies, we could purchase war stamps to paste in that book. Talk about pride! Each stamp in my book was proof that I was helping our soldiers.

Another school practice made us war conscious. Whenever a convoy of recruits passed by on the way to shipping out, students in the upper grades would march outside to the fence bordering the Spartanburg (SC) Highway. There they waved and yelled to the soldiers until they were out of sight. We first-graders could simply watch from the classroom windows. Occasionally, the convoy would stop, and the young privates would walk along the fence thanking the boys and girls. Older girls became pen-pals with young, enlisted men. Often more than one letter from a lonely GI would arrive simultaneously by way of V-mail.

Daddy’s desire to support the war effort convinced him to move north near Washington, DC, to work at an industrial plant. He was a tinsmith, but he was adept at using various kinds of machinery. I was never told exactly what his job was. Perhaps he helped manufacture parts to use in tanks, airplanes, or ships. Mother decided it was best that “Bubba” and I not change schools, and she kept us at home in East Flat Rock. Daddy returned occasionally and shared his experiences, such as visiting the White House and the Senate.

During those days, Daddy would drive us around nearby Hendersonville in the evenings. Peggy and I became curious about blue stars hanging in the front windows of houses we passed. Our folks explained that the family living there had a son fighting for our country. Later I learned that if a soldier were killed, a gold star would replace the blue one. (Years later, I learned that my friend Margurette Dickson Summey’s husband and his entire crew disappeared on a raid near Bingen, Germany. She grieved that their bodies were never recovered and that the Red Cross failed to notify John of their son’s birth.)

Attending church on Sundays made me even more conscious of the war. The congregation offered prayers for the “boys” overseas and for President Roosevelt. Sometimes the pastor invited the men of the church to cluster at the front bench and pray for the servicemen and their families. Although I did not understand the trials of war, I felt sad listening to those petitions.

There were multiple ways to support the war effort. My brother collected scrap metal and glass to be recycled and sold. The fragments were dropped off at the local school and hauled away. Money from such sales helped to build warships or to support wounded soldiers. Women in our community learned to knit socks to warm a soldier’s feet. Those women took pride in their work, but they often complained about the task of “turning the heels.” Extra footwear to replace worn or wet socks brought comfort to men fighting in Europe.

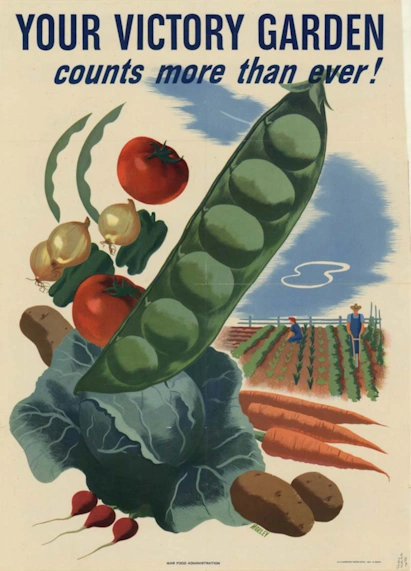

To support the war effort, the government encouraged gardening. Our family and close neighbors had always planted a garden and fields of corn, but quite a few folks in Hendersonville cultivated “victory” gardens to support the war effort. They raised beans, squash, greens, lettuce, carrots, radishes, and potatoes. In theory, their effort allowed a greater abundance of food to be shipped to the fighting men.

Image Credit

Image Credit

I cannot recall a time when words did not interest me, and my vocabulary grew by leaps and bounds during the war. Expressions like kamikaze, swastika, genocide, displaced persons, and death camps stirred my curiosity. I could not understand how a “person” could be “displaced,” and were there camps where folks went to die? But, as I grew older, I gradually came to understand what those expressions meant. News of atrocities targeting Jews sifted through my consciousness. Nearby Hendersonville had been home to a synagogue since the early 19th century, and our family often shopped in stores owned by Jewish merchants.

Image Credit

Image Credit

Posters of Uncle Sam with his message “I Want You” were common. My cousins had enlisted in the Army and in the Marines and were serving overseas in Europe and in the Pacific. Then, at the end of the 11th grade, my brother William graduated from Flat Rock High School. Within a short time, he received orders to report to the training center for the United States Navy. Not yet 17 years old, he forged our father’s name on the recruitment papers.

After dropping him off at the bus station, our folks returned home to find orders for William to report to the United States Marines. That created a dilemma for my parents. Uncertain about what action was needed, they visited the local Post Office to ask Postmaster John E. Creech for help. With his assistance, my parents sent a message to the United States Marine recruiter, and the problem was solved.

Later my folks learned their son had applied to each branch of service. Like other young men, he was determined to serve. Because he had flat feet, the Army turned him down. (Young men rejected by the armed forces for physical reasons were classified as 4-F and were often ridiculed. Being deemed “unfit for military service” forced them to find other ways to serve. As an adult, I learned youthful women were thankful those men had been left behind; eligible men to date were in short supply on the home front.)

Following basic training, my brother came home on furlough, and the meal Mother prepared was equal to “dinner on the grounds” at church. Baked ham and fried chicken, potato salad, chocolate cake, and lemon meringue pie were part of the grand meal. Upon returning to base, William was assigned to an office located on an island not far from Fort Pierce, Florida. In high school, he had learned to type and to take shorthand−−probably because, by signing up for such classes, he got to sit alongside the girls he hoped to date. His first naval assignment consisted of typing all day long, which was not what he had enlisted for. He wanted to see “action.” By some means, he succeeded in being reassigned to the USS Douglas Fox Destroyer. There he was much happier.

The destroyer’s home port at that time was Norfolk, Virginia. In the Caribbean, her crew served guard duty for airplanes. My brother wrote home often but was forbidden to reveal his location. Once, he announced that he was sending a crate of oranges to Peggy and me. We were so excited. Our Christmas stockings usually contained one orange, and that was a precious gift. It was hard to imagine an entire crate of delicious fruit. When a package from “Bubba” finally arrived, we fought over who could open it −− scratching, pulling hair, pinching, and delivering blows to one another beneath the huge oaks in our front yard. Mother finally intervened, pulled us apart, and opened the package, which contained several presents, including one tiny crate-like container of orange-colored gumballs. Bubba had tricked us, and we remained angry at him for quite a while.

One afternoon our neighbor Molly Justus came with the news that our brother’s ship was featured on the front page of the Hendersonville newspaper. As soon as possible Mother purchased the paper and eagerly read about the USS Douglas Fox Destroyer, pleased that her son was serving aboard that vessel. Each of us was proud of that picture.

On board the Douglas Fox William crossed the Equator for the first time. All newbies on the destroyer were “initiated” to commemorate their first crossing. Part of that initiation was having “garbage” shoved into their mouths while they were blindfolded. William had a weak stomach; what he believed to be catguts were forced past his lips and onto his tongue. To the delight of the crew, he threw up, and then he was tossed into a tank of water, even though he could not swim. He survived because soon he was dog-paddling.

Then in February 1945, the destroyer pulled into port at Rio de Janeiro. My brother thought it was the most beautiful place he had ever seen and vowed to return there one day. He bought each of us a gift, and we were thrilled to receive them. In one letter William reported that their crew had rescued a pilot who had been forced to ditch his plane at sea.

Although common today, divorce was not an everyday event when it invaded our family in the 1940s. My uncle moved away to work in a defense plant. While there, he fell in love with another woman and asked my aunt for a divorce. His family was heartbroken, and my folks were sad. While the divorce proceedings, which took far longer than a year, were ongoing, a sense of grief overshadowed family gatherings. My folks mourned the death of a marriage, which troubled Peggy and me. No one in our family had ever divorced his wife. The final decree terminating the marriage created a great deal of unhappiness, but eventually that aura of grief faded.

Then a bit of romance came to our family secondhand. My cousin Frances Case boarded a Trailways bus headed to Norfolk, Virginia. At one stop a young serviceman, C.H. Fisher, took the vacant seat beside her, and they talked to one another for the next one hundred miles. C.H. served at the Oceana Naval Base in Virginia Beach, and the couple exchanged letters and saw one another from time to time. They married on October 11, 1946. Their marriage endured 60 years ending with Frances’s death on May 24, 2006.

Another death stands out in my memory. President Roosevelt, whom my parents admired, died in April of 1945, and Vice President Truman took over. One day Molly Justus brought us her signature egg custard in a glass quart jar and announced that the war had ended. People poured into town and drove up and down Main Street blowing their horns. Shouts of “Our boys are coming home!” accented a joyful day. It was a happy and exciting time. After that, there was even more reason to go to the theater for news updates.

Following the defeat of Hitler’s forces and the dropping of the atomic bomb, all fighting ceased. World War II ended. Gromer came home from Pearl Harbor. Soon William was discharged. He and our cousins returned safe and unharmed, but the sons of other community members did not. Ninety-one men from Henderson County died during the war. One was my husband’s uncle, Judge Dick King (1922-1944). Uncle Dick was the son of William and Ann Esther King. He was killed in action as his unit spearheaded the D-Day landing on Utah Beach in 1944, not far from Paris, France. Uncle Dick’s gravestone is at the Normandy American Cemetery, Colleville-sur-Mer, France (https://hendersonheritage.com/world-war-ii-heroes/). His brothers survived the war.

Although residents in East Flat Rock celebrated the war’s end, they grieved for the young men who perished. During those days I had few memories of a time without war, but peace brought new prosperity and created a strong sense of satisfaction because the world was at peace. Rationing did not immediately cease, but life was easier, and Daddy moved back home.

War material was no longer needed and became available to the public. Among those items were silk parachutes which women purchased to make undergarments, slips, and blouses. One young lady in our community, Frances Stepp, created her wedding gown from a parachute, and in recent years donated that dress to the Henderson County (NC) Historical Society. It is now on display at the old Court House on Main Street. [That bride, Frances Stepp Bokirk, died on September 15, 2021, at the age of 101.]

One day Mother needed to go to the Post Office in East Flat Rock. Peggy and I rode in the backseat while Gromer sat in front. Before a mile passed, Mother was forced to pull to the side of the Spartanburg Highway because the road was swarming with marching men. She soon realized a group of German prisoners of war was passing by. Those POWs were being escorted by American soldiers to the fairgrounds where they would live in specially prepared huts. Once Gromer realized German soldiers were trudging past us, he scooted his body through the car window and sat straddling it with his legs inside and his arms on top of the parked car. Much to Mother’s horror, he would occasionally raise an arm in salute and shout, “Heil, Hitler!” The prisoners did not respond but kept marching by.

Later the Germans rode in trucks around the countryside, even down into South Carolina, to work on farms, picking beans, pulling corn, and digging potatoes. They received pay in exchange for their labor. Prisoners earned a stipend of $.85 a day for their work. Which is equivalent to $16 today. Such a sum allowed laborers to buy an occasional treat. The C.M. Jones family lived directly across from the prison camp, and their young son Woody converted a small building into a makeshift grocery store. There the German prisoners, accompanied by guards, bought candy bars, Cokes, and other items. Today a senior citizen, Woody states that he never saw a happier group of people. Thinking back to those days, I believe the German soldiers were even happier for the war to end than we Americans. Perhaps being prisoners on foreign soil was better than being targets on European battlefields.

A local farmer, Claude Morrison, had designated one of his fields for making hay. A strong storm blew in and twisted the grass to the point that it was impossible to use his sickle mower. He arranged to hire POWs to cut the grass by wielding scythes. The officials who assigned prisoners to local jobs required that an armed sentry guard them. Morrison’s neighbor, Allan Reed, armed with a shotgun, watched the prisoners while they cut the grass and stacked it in shocks. Such backbreaking labor, swinging scythes through the twisted vegetation, required periods of rest, and the prisoners “chatted” with Allan, eagerly sharing snapshots of their girlfriends and families. Despite the language difference, their English words, facial expressions, and hand gestures provided a way to communicate. A few prisoners quickly grasped our language, and others spoke at least a smattering of English. According to Woody Jones, their American guards did not speak German. From 1942 through 1945, more than 400,000 Axis prisoners were shipped to the United States and detained in camps in rural areas across the country.

Watching those soldiers march from the train depot past our car was not our family’s. final experience with the prisoners of war. Occasionally the young men−unguarded−would walk past Rozier’s Curve on their way to the depot, to the grocery store, or to the post office in East Flat Rock. [POWs were allowed mailing privileges; they could send two letters and four postcards each month free of charge; there was no limit on incoming mail (National Postal Museum. (n.d.). Military personnel free frank.). From time to time one of the prisoners would stop at our house to smile at Peggy and me, in a teasing fashion, and to speak to Mother. I cannot recall any of their conversations. Before leaving, the young man might ask for a drink of water, occasionally using his hands to point at his mouth and at the well. Mother kept a bucket of water with a dipper nearby. The young man would drink from our dipper and thank her. In retrospect, I wonder if they enjoyed interacting with an American family in a normal setting, especially a family with young children. Peggy and I looked forward to having them drop by. I suppose we stared at them, but they didn’t seem to mind.

One day the prisoners were gone−they had disappeared, vanished. Perhaps, with winter approaching, they were transferred to pick oranges in Florida. Eventually, they returned to their homes. One man traveling in Germany recognized a fellow who had worked on his farm, and they spoke briefly about the past. Later Moby Sorrells of Brevard, North Carolina, told of German soldiers picking cabbages on his father’s land. He also revealed that one Transylvania County (NC) native kept in contact with a former POW for several years. Their absence created a fleeting moment of wonder in my 8-year-old mind, but I was engrossed in schoolwork and exploring creeks, swamps, and the woods near home. As a teenager, I heard rumors that a few prisoners had returned to live in the United States because their homes in Germany had been destroyed.

When I was in the seventh grade, our teacher, Mamie Wells, told our class that when World War II first broke out, a group of citizens in Hendersonville gathered outside a business owned by German immigrants demanding they shut down their business and leave. Mrs. Wells was ashamed of that action, and she succeeded in making our class feel the same way. Not all Germans were NAZIs who supported Hitler. I believe many youthful Germans were forced into military service against their will. Among my favorite memories of World War II are my brief encounters with those young soldiers, but I rejoiced with other residents in East Flat Rock as the war faded away. Subconsciously I endorsed the absence of war as “good riddance.”